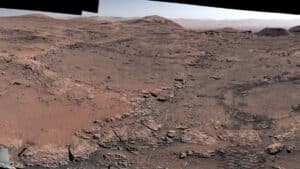

The underwater archaeological discovery off Indonesia’s coast has revolutionized our understanding of prehistoric Southeast Asia. In 2011, marine sand mining operations between Java and Madura islands unearthed remarkable findings that scientists have only recently verified. This groundbreaking site represents the first underwater hominin fossil discovery in the region, providing tangible evidence of Sundaland, the ancient landmass that once connected much of Southeast Asia.

Unveiling the submerged prehistoric landscape

The extraordinary findings near Surabaya have revealed a 140,000-year-old underwater world that once thrived as part of Sundaland. Archaeologists led by Harold Berghuis from the University of Leiden confirmed that two human skull fragments—frontal and parietal—belong to Homo erectus specimens. These remains lay preserved beneath ocean sediment for approximately 140,000 years until sand mining operations accidentally recovered them.

Using Optically Stimulated Luminescence (OSL), researchers dated the site to between 162,000 and 119,000 years ago. This technique measures when sediment last received sunlight exposure, providing reliable age estimates for the recovered materials. Geological analysis has uncovered evidence of an ancient river system that once flowed across what scientists now call the Sunda Shelf.

The research team identified the remnants of the prehistoric Solo River, which created a vibrant ecosystem during the late Middle Pleistocene. Rising sea levels between 14,000 and 7,000 years ago eventually submerged this entire region. Scientists estimate that melting glaciers from the final Ice Age raised ocean levels by more than 120 meters, drowning Sundaland’s low-lying plains and separating the Southeast Asian mainland from its islands.

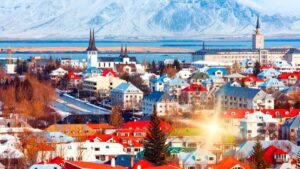

In 2019, Iceland Approved the 4-Day Workweek: Nearly 6 Years Later, All Forecasts by Generation Z Have Come True

At 94, He’s One of Apple’s Biggest Shareholders, and Doctors Can’t Explain How He’s Still Alive-Coca-Cola and McDonald’s Are Part of His Daily Routine

Remarkable biodiversity and extinct megafauna

The underwater excavation yielded over 6,000 vertebrate fossil specimens representing 36 different species. This remarkable collection includes:

- Komodo dragons

- Ancient buffalo species

- Multiple deer varieties

- Stegodon, an extinct elephant-like creature

- Various savanna-dwelling herbivores

The presence of Stegodon fossils particularly excited researchers. These massive herbivores stood over 13 feet tall and represented a dominant megafauna species in prehistoric Southeast Asia. The fossil assemblage suggests the area resembled a savanna rather than dense jungle, supporting diverse herbivore populations and their predators.

The abundance of antelope-like species, which typically prefer open grasslands, further supports the savanna ecosystem hypothesis. This environment would have provided ample food resources for both animals and early human populations inhabiting the region.

| Fossil Type | Quantity Found | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Homo erectus skull fragments | 2 | First underwater hominin fossils in Southeast Asia |

| Animal remains | 6,000+ | Evidence of biodiversity and ecosystem |

| Species represented | 36 | Indicates rich environmental conditions |

It races through the universe at 300,000 km/s - and never runs out of energy

Beneath your feet: an ancient forgotten continent resurfaces in Europe

Early human technological advancement

Perhaps most fascinating are the cut marks discovered on many animal bones. These distinct markings provide compelling evidence of deliberate butchery practices by early humans. According to Berghuis, “This period is characterized by great morphological diversity and mobility of hominin populations in the region.”

The butchery evidence suggests Homo erectus groups in Sundaland employed relatively sophisticated hunting and processing techniques. These early humans, characterized by their taller stature, longer legs, and shorter arms, had physical proportions more similar to modern humans than earlier hominin species.

The Madura Strait findings significantly expand our understanding of Homo erectus distribution throughout Southeast Asia. Their presence across Sundaland offers fresh perspectives on early human migration patterns and adaptive strategies in response to changing landscapes and environmental conditions.

What began as an accidental discovery during industrial operations has transformed into a pivotal archaeological breakthrough. By integrating archaeological, geological, and paleoenvironmental methodologies, scientists continue uncovering this submerged chapter of human evolution that remained hidden beneath Indonesian waters for over 140,000 years.