The archaeological world is buzzing with an extraordinary find that challenges our understanding of early tool use. In southwestern Kenya, researchers have unearthed stone tools dating back approximately 3 million years, potentially making them the oldest Oldowan tools ever discovered. What makes this finding particularly remarkable isn’t just their age, but who may have created them.

Ancient tools reveal unexpected toolmakers

For decades, scientific consensus held that only members of the genus Homo possessed the cognitive capabilities to create stone tools. This assumption is now being questioned following excavations at the Nyayanga site near Lake Victoria. Between 2014 and 2022, archaeologists recovered more than 300 stone implements alongside fossils of Paranthropus, a robust hominin species not directly ancestral to modern humans.

“We’ve always associated toolmaking exclusively with our direct ancestors,” explains Thomas Plummer, anthropology professor at Queens College and the study’s lead author. “Finding these tools with Paranthropus fossils forces us to reconsider which species were capable of creating and using stone technology.”

The tools, predominantly crafted from quartz and rhyolite, belong to the Oldowan tradition—previously dated to around 2.6 million years ago based on Ethiopian discoveries. This new find potentially pushes that timeline back by 400,000 years, representing a significant adjustment to our archaeological chronology.

The discovery challenges long-held beliefs about Paranthropus, whose massive jaws and teeth were thought to eliminate their need for tools. Evidence now suggests these robust hominins may have been more technologically adept than previously recognized.

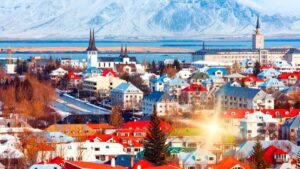

In 2019, Iceland Approved the 4-Day Workweek: Nearly 6 Years Later, All Forecasts by Generation Z Have Come True

At 94, He’s One of Apple’s Biggest Shareholders, and Doctors Can’t Explain How He’s Still Alive-Coca-Cola and McDonald’s Are Part of His Daily Routine

Evidence of advanced food processing capabilities

Perhaps most striking about the Nyayanga discoveries is the presence of hippopotamus bones bearing distinct cut marks from stone tools. This evidence indicates that whoever wielded these implements—possibly Paranthropus—was capable of processing large animal carcasses for consumption.

Emma Finestone, a paleoanthropologist from the Cleveland Museum of Natural History involved in the research, notes: “The association between Paranthropus fossils and butchered animal remains represents a paradigm shift in our understanding of early hominin behavior.”

Whether these ancient toolmakers were active hunters or opportunistic scavengers remains unclear, but their capacity to harvest meat from creatures as substantial as hippopotamuses demonstrates unexpected sophistication. This challenges previous assumptions about the dietary and technological capabilities of non-Homo hominins.

The Oldowan toolkit, while simple by modern standards, represented a revolutionary technological advancement that included:

- Hammerstones for striking flakes

- Sharp-edged flakes for cutting

- Cores from which flakes were removed

- Possible scraping implements

It races through the universe at 300,000 km/s - and never runs out of energy

Beneath your feet: an ancient forgotten continent resurfaces in Europe

Implications for understanding hominin evolution

This discovery has profound implications for our understanding of cognitive evolution among early hominins. The table below illustrates how this finding reshapes our timeline of technological development:

| Time Period (Years Ago) | Previous Understanding | New Understanding |

|---|---|---|

| 3 million | No known stone tools | Oldowan tools possibly made by Paranthropus |

| 2.6 million | Earliest Oldowan tools (Ethiopia) | Oldowan tradition already established |

| 2 million | Tools exclusively made by Homo species | Multiple hominin genera potentially making tools |

The conventional narrative of human evolution has often portrayed technological innovation as a linear progression tied specifically to our direct ancestors. However, the Nyayanga findings suggest a more complex picture where multiple hominin species independently developed or shared tool-making capabilities.

This research opens exciting new questions about interactions between different hominin species. Did knowledge transfer occur between groups? Did tool use evolve independently multiple times? These questions will drive further investigation into our ancient past.

As we continue to unearth evidence from this critical period of human prehistory, one thing becomes increasingly clear: the story of technological development is far more intricate than previously believed, with multiple branches of the hominin family tree contributing to the emergence of stone tool technology that would ultimately help shape human destiny.